Subtle Moonlighting At Work: The “Nice” Behaviors That Quietly Cost Time, Create Pressure, And Sometimes Trigger Real Liability

- TheFitProfessional1

- Jan 9

- 9 min read

By Paul Ayres

Executive Summary

Subtle moonlighting rarely announces itself as a problem. It arrives disguised as goodwill fundraisers for kids’ teams, “free” professional services attached to holiday gifts, charity links in work chats, or side businesses quietly promoted among colleagues. Yet research consistently shows that these small, well-intended behaviors carry outsized consequences. Studies on workplace giving and social influence find that visible or peer-driven solicitation can increase participation by 20 to 40%, not because employees want to give more, but because they feel social pressure to conform. At the same time, research on side hustles and attention residue shows that even brief non-work interruptions can reduce task focus and cognitive performance, especially when they are repeated across the workweek.

The impact is not just personal discomfort; it is organizational. A two-minute diversion repeated across meetings, emails, and follow-ups can quietly consume dozens of hours per month in a mid-sized team. More critically, labor-law precedent shows that inconsistent tolerance of “harmless” solicitation, charitable or otherwise, has been used as evidence in legal disputes when employers later attempt to restrict other forms of solicitation. What begins as kindness can end as inconsistency, resentment, or exposure.

This Article:

Clarifies how to identify subtle moonlighting using observable signals rather than intent.

Explains why certain behaviors can feel coercive even when labeled “voluntary."

Shows how leaders can protect workplace culture without becoming overly restrictive.

Concludes with a Practical Action Plan to:

Establish clear boundaries around work time and work resources.

Prohibit supervisory solicitation.

Confine any permitted personal announcements to a single, neutral channel.

Remove personal or business promotional items from workplace gifts and celebrations.

When paired with a simple manager script, these steps preserve generosity while safeguarding focus, fairness, and trust.

The takeaway is direct: organizations do not need to eliminate humanity at work, but they do need to prevent the workplace from becoming a marketplace. Clear boundaries reduce pressure, reclaim time, and reinforce a culture where belonging is never something employees feel compelled to buy.

The Modern Definition: “Non-Work Value Exchange Inside Work Systems”

A workable definition of subtle moonlighting is this:

Any non-job value exchange money, services, memberships, donations, or leads that is initiated, promoted, coordinated, or delivered through work time, work tools, work relationships, or work spaces.

That definition covers the obvious “selling cookies in the breakroom,” but it also captures the genuinely tricky cases: the ones wrapped in generosity, gifts, or social belonging.

Consider a scenario that shows up every December in well-meaning organizations.

An employee gives everyone a company Christmas gift, something kind, seemingly harmless. But tucked into the gift is an “extra”: a voucher for the employee’s side business. Maybe it’s “a free 30-minute financial consult,” “a complimentary photography mini-session,” “a free detail for your car,” or “a free home inspection add-on.”

It’s presented as generosity, but it’s also a funnel: it brings colleagues into a paid service relationship later, and implicitly uses workplace goodwill as a marketing channel.

Even if the initial service is genuinely free, the workplace is being used to create a customer base. And the recipient isn’t receiving a neutral offer; they’re receiving it inside a relationship where refusing can feel awkward, ungrateful, or risky.

That is subtle moonlighting in its purest form: “gift-wrapped solicitation.”

Why It Matters: Two Harms Leaders Systematically Underestimate

Attention residue: The invisible productivity tax

Side activity doesn’t have to take hours to cost hours. Side-hustle research and practitioner synthesis consistently point to a distraction pathway: even when the extra work isn’t performed during work hours, it can create ongoing cognitive load and attention spillover.

Now apply that mechanism to workplace solicitation and micro-commerce. The moment someone sees the message, the flyer, the QR code, the “hey, quick question,” they’re forced into a mental workflow: decide, budget, respond, manage the relationship. That’s attention residue, and it scales.

A two-minute interruption repeated across a department, a week, and multiple causes is not “small.” It’s operational friction.

Social pressure: The culture tax

Workplace giving and workplace buying are not the same as giving and buying elsewhere. The workplace has hierarchy, repeated interactions, and reputational consequences. Behavioral research on charitable giving in workplace contexts finds that social influence meaningfully shapes participation and giving behaviors, which means “voluntary” can become “reluctant” faster than leaders realize.

This is exactly where the kids’ athletics fundraiser becomes tricky. In many teams, one ask isn’t the problem. The problem is the felt obligation, especially for employees who already donated elsewhere, are budget-constrained, are private about finances, or simply want to keep work about work.

A healthy culture cannot require people to purchase belonging.

The Borderline Examples That Most Often Create Discomfort (And Hidden Waste)

Here are common scenarios that meet the “Non-Work Value Exchange Inside Work Systems” definition. I’m describing them as they actually occur, not as policy hypotheticals.

The fundraiser drumbeat.

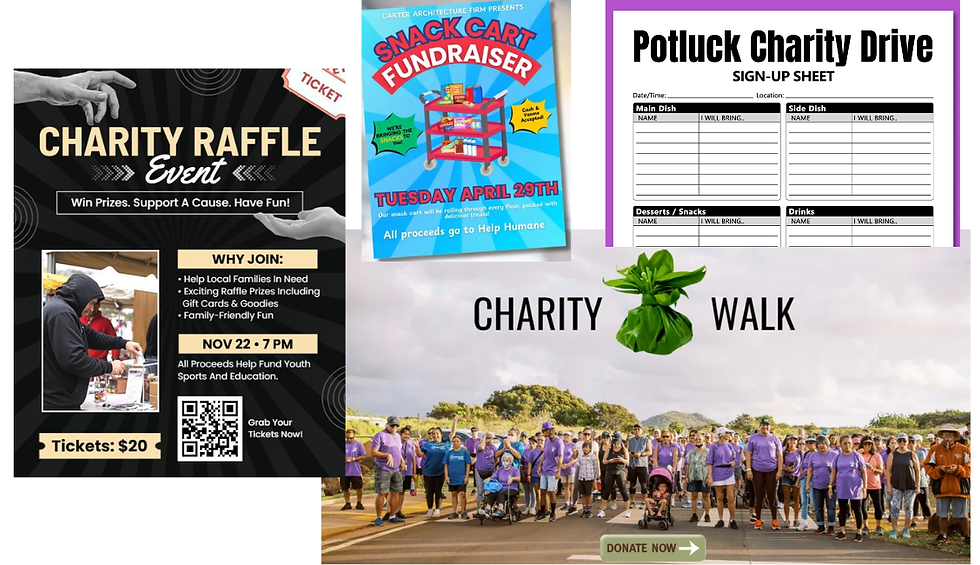

A raffle, a sports team fundraiser, a GoFundMe, a charity walk: not one announcement, but repeated reminders, tracking, follow-ups, and “last chance” nudges, often in group chats or workplace email. This often creates pressure on people who already gave at home, who feel tapped out, or who don’t want their spending choices visible.

The “free service” gift that’s really a lead generator.

The Christmas gift add-on described above is the cleanest example. It’s hard to refuse, easy to accept, and it can become a pipeline that uses workplace relationships as the marketing engine.

The office micro-market.

Tickets, products, subscriptions, cookies, meal kits, services, sometimes small, but frequent. The bigger problem is not the sale; it’s the normalization of sales behavior inside work relationships.

The cause carousel.

Today it’s a community tragedy. Tomorrow it’s a charity. Next week, it’s someone’s medical bill. Leaders want to be compassionate, and they should be, but repeated workplace solicitation can also become a pressure engine and a trust issue, especially when participation becomes visible.

The “opt-in” that doesn’t feel opt-in.

A manager says, “No pressure,” then publicly thanks donors, posts names, or offers social recognition in a way that subtly labels non-participants. That’s the moment “nice” becomes coercive.

A Simple Way to Determine Impact Without Arguing Motives

The biggest mistake leaders make is debating intent:

“They’re just being nice.” Impact is what matters.

A practical determination standard is to look for these signals:

It appears during working hours or during meetings.

It uses work channels (Email/Teams/Slack), workspaces, or work equipment.

It repeats, follow-ups, reminders, “final notices,” and targeted nudges.

There’s a power dynamic: a supervisor, a team lead, a high-status peer.

Participation is visible: donor lists, public shout-outs, leaderboards.

People complain, or they silently avoid the asker, the space, or the channel.

When multiple signals appear, you’re no longer talking about “a kind gesture.” You’re talking about an unmanaged workplace system that consumes time and produces discomfort.

Two “Seemingly Harmless” Situations That Produced Real Legal Consequences

These are not “kid fundraiser” cases by name. They’re more instructive: they show how small, ordinary allowances around solicitation can trigger serious workplace legal disputes, especially under labor law, if policies are inconsistent.

1) Charitable solicitation exceptions that become evidence of discrimination

In Albertson’s Inc. v. NLRB (6th Cir. 2002), the court addressed how allowing some charitable solicitation can interact with rules restricting other solicitation. The decision discusses, among other things, the idea that an employer may allow a limited number of isolated charitable solicitations, often described as a narrow “beneficent acts” allowance, without automatically being treated as unlawfully discriminatory in other contexts.

This is the key workplace consequence: once you open the door to workplace solicitations, you create a policy enforcement problem. If your organization later restricts other kinds of solicitation (especially in union/organizing contexts), those “harmless” charitable allowances can become central evidence in a legal challenge about discriminatory enforcement.

2) “It’s just cookies” becomes part of a property-access legal framework

In Kroger Limited Partnership I Mid-Atlantic (NLRB, 2019), the Board clarified when non-employee union agents may be excluded from employer property and how “discrimination” is evaluated in access disputes.

Around the same era, decisions and commentary (including widely discussed examples such as allowing Girl Scout cookie sales or other community/charitable activities while excluding union activity) helped sharpen the distinction between “comparable activities” and what counts as discriminatory treatment.

Again, the point is not cookies. The point is that seemingly harmless solicitation practices that get to ask, what gets to be promoted, and what the organization tolerates can become the backbone of legal arguments when conflicts arise. And once you’re in that posture, “we were just trying to be nice” isn’t a defense; consistency is.

A Culture-Preserving Policy Stance That Actually Works

HBR’s side-hustle guidance and broader HR practice writing converge on a balanced posture: don’t try to control employees’ lives, but do control work time, work tools, work relationships, and conflicts of interest.

Here is the practical translation for subtle moonlighting and workplace solicitation.

A healthy workplace can be warm without turning into a marketplace. The goal is not to ban kindness; it’s to remove coercion and friction.

That means three non-negotiables:

1) Voluntary must be real.

No tracking donors. No praise that implies moral superiority. No public lists. No “participation goals.” And supervisors should not solicit direct reports for money or purchases, ever. The NLRA’s core principle against interference and coercion is not a technicality; it’s a reminder that power dynamics matter at work.

2) Bound the channels.

If the organization allows any fundraising or personal announcements, confine them to a single controlled lane: one bulletin board, one monthly community note, one HR-managed channel with strict frequency limits. Otherwise, solicitation will creep into meetings, chats, and workflows because it’s convenient, and convenience is how culture drift happens.

3) Bound the resources.

No company email lists, no printers, no internal distribution systems, no customer/vendor lists, no meeting time. The side hustle can exist, but the company cannot be the delivery mechanism. This is consistent with mainstream employer guidance on moonlighting risk: conflicts, resources, and performance are the levers employers can legitimately manage.

How the “Free Service Gift” Should Be Handled (Without Humiliating Anyone)

If someone adds a “free service voucher” to a company holiday gift, treat it as a courtesy and clearly indicate it.

You don’t need a moral lecture. You need a boundary: “We appreciate generosity, but we don’t allow personal business promotion through workplace gifting. Gifts should not contain offers that create future paid relationships with coworkers.”

Why? Because it creates a subtle pressure loop:

“Accept the voucher, and you feel obligated.”

“Don’t accept, and you feel ungrateful.”

“Accept and then decline later, and you risk relationship awkwardness.”

That dynamic is the opposite of psychological safety (and without needing that phrase, it is the opposite of a workplace that respects personal boundaries).

It also creates fairness issues: employees without side businesses don’t get an equivalent marketing opportunity. Over time, employees start to wonder which relationships at work are genuine and which ones are transactional. That is not a small cultural cost.

Closing Thought: Clarity Is Kindness, Especially in the Gray Areas

The best organizations don’t try to litigate every human impulse. They do something simpler and more humane: they name the gray area, explain the “why,” and make the boundary easy to follow.

If the workplace becomes a stage for personal selling, personal fundraising, and personal service pipelines, even when presented as kindness, employees pay attention and feel discomfort. Leaders pay in inconsistency and risk. And the organization slowly drifts from “good place to work” to “place where you have to manage other people’s asks.”

Culture is not built by how many causes you promote at work. It’s built on how reliably you define and enforce boundaries so that awkward workplace pressures don’t create cultural friction.

Paul T. Ayres

Business, Executive, Leadership & Life Coach

Email: paul@thefitprofessional1.com

Website: www.thefitprofessional1.com

Connect with me on socials!

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/fitpro1coach/

Professional Bibliography

Ayres, P. THEFITPROFESSIONAL1™. Practitioner frameworks and leadership guidance.

Albertson’s Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 301 F.3d 441 (6th Cir. 2002). (Case text via Justia.) Justia

Faegre Drinker (Faegre & Benson LLP). “Charitable Fundraising Could Imperil Your Company’s Union-Free Status.” Faegre Drinker Insights, 2001. Faegre Drinker

Harvard Business Review. “When Can You Fire for Off-Duty Conduct?” Harvard Business Review, 1988. Harvard Business Review

Harvard Business Review Publishing (HBSP case). “Allow Ethical Moonlighting Or Lose To Gig Working?” Harvard Business School Publishing, 2023. (PDF product listing; 10 pp.) Harvard Business School

Jennifer D. Nahrgang; Hudson Sessions; Manuel J. Vaulont; Amy L. Bartels. “Make Your Side Hustle Work.” Harvard Business Review, 2020. MIT Sloan

Kroger Limited Partnership I Mid-Atlantic and United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 400, 368 NLRB No. 64 (Sept. 6, 2019). (Decision and Order PDF.) calfee.com+1

National Labor Relations Board. “Interfering with employee rights (Section 7 & 8(a)(1)).” NLRB.gov, undated page (accessed 2025). National Labor Relations Board

Sanders, M., et al. “Social influences on charitable giving in the workplace.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 2017. TIJER Research Journal

UPMC and its Subsidiary, 368 NLRB No. 2 (June 14, 2019). (Decision PDF.) managementmemo.com+1

Xu, Q., et al. “Voluntary or reluctant? Social influence in charitable giving.” PubMed Central, 2023. Ogletree

Forbes Technology Council. “Sunlighting Vs. Moonlighting: Ethics And Guidelines For Additional Work.” Forbes, 2023. pollardllc.com

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Allen Smith, J.D. “Review Moonlighting Policies in Light of Remote Work, Inflation.” SHRM, 2022.

Littler Mendelson. “Dear Littler: … prohibit employees from ‘moonlighting’?” Littler, Aug. 19, 2024. Littler Mendelson P.C.

U.S. Office of Personnel Management / eCFR. “5 CFR Part 950 — Solicitation of Federal Civilian and Uniformed Service Personnel for Contributions to Private Voluntary Organizations.” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Law Offices of Matthew Johnston

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Fundraising for Your Favorite Cause? Know the Ethics Rules Before You Do.” DOI Ethics, 2021.

U.S. Department of Defense Office of the General Counsel. “Fundraising.” (PDF guidance referencing 5 C.F.R. Part 950), 1997. dodsoco.ogc.osd.mil

Comments